|

Enter content here The Constantine Institute |

.

The Dignity for All Students Act

|

|

|

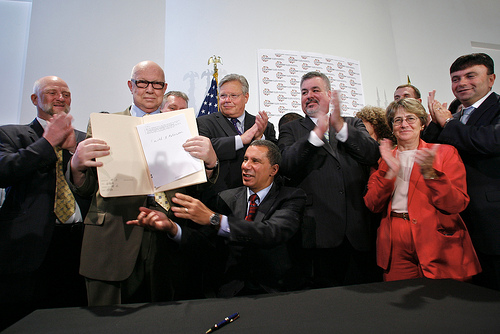

Enter subhead content here Remarks Terry O’Neill, Director The Constantine Institute, Inc. 36th Annual Law Youth and Citizenship Conference New York State Bar Association Lake George NY 19 October 2012 The Dignity for All Students Act -- How We Did It In July 2004, New York City’s Brennan Center for Justice released its landmark report The New York State Legislative Process: An Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform and the word “dysfunctional“ entered the vocabulary of New York’s political discourse. The report concluded that the Legislature had evolved into a body so closed and unrepresentative that it could not solve problems, do simple business or allow meaningful participation of the public in the making of public policy. In short: it was incapable of providing the people with effective government. I’ve been involved in the legislative process since I went to work as Counsel to Brooklyn Assemblyman Edward Griffith in January 1984. In my experience, the Legislature is dysfunctional only if you want it to be. And believe me, Albany is populated by thousands of individuals and organizations who have an abiding vested interest in staving off the solution of problems. They live off problems. They are lobbyists, careerist legislators and legislative staff and a variety of advocates and advocacy groups who are part of the permanent subculture collectively known as Albany. As I say, the Legislature is dysfunctional only if you want it to be. The statute we are here to discuss today is an example of what is possible if people who have no patience with what Governor Andrew Cuomo has called “the Albany game” can achieve. The fact, however, that it took eleven years to get the Dignity for All Students Act onto the governor’s desk in this particular case actually worked very much in favor of those of us who were working to address the problem of bullying and discrimination. I’ve had a long string of stunning legislative successes over the years. Each one came about through very unique circumstances and involved the crafting of strategies that took advantage of the opportunities that each case presented. Let me give you two examples. In the late summer of 1993, a little girl named Sara Anne Wood was snatched off a country road in Herkimer County. Although the State Troopers eventually caught the guy -- one Lewis Lent -- who took her, we have never found her. Lent is in prison and saying nothing. Over the winter of 1993-94, the Troopers engaged in a massive search for Sara Anne. The case generated enormous publicity in Upstate New York. I was at DCJS at the time and one of our programs, the Missing and Exploited Children’s Clearinghouse, attracted lots of media curiosity. Diane Vigars, a lovely lady who had run the program in obscurity for many years, stopped me one morning and told me that the publicity had led to a number of calls from the public with offers of financial support for the work of the clearinghouse which, by the way, found an average of one missing kid a week.. “That’s wonderful!” I said. “No it isn’t,” she replied. “The bosses won’t let us take the money.” Well, I went right down to the “dysfunctional” Legislature, to the office of Senator Dean Skelos, to be specific. Within a day, we had drafted and he had introduced what came to be the Missing and Exploited Children’s Clearinghouse Fund Act of 1994 -- essentially a bank account to accept those donations “the bosses won’t let us take.” By 2000, that fund had a balance of $1.2 million. Today, I’m told that it takes in about $300,000 a year. In January 1998, I got a call from my best friend Paul Richter. In September 1973, Paul was on patrol as a State Police Zone Sgt. just outside Lake Placid when he was shot by two guys who had just stolen a quantity of handguns from a sporting goods store. Paul spent a year almost completely paralyzed. He’s recovered somewhat, but has lived with paralysis ever since. He had called to ask if I thought we could persuade the “dysfunctional” Legislature to pass a bill that would impose a small surcharge on V & T Law (i.e. speeding tickets) fines that would go into a trust fund from which paralysis research grants to medical facilities around the state might be awarded. I looked into it and came to the conclusion that it was well worth a try. And so we set about building a coalition of highly motivated people who could help us draft a bill then lobby for its passage. The bill was introduced in April and signed by Governor George Pataki in July. It created the Spinal Cord Injury Research Program (SCIRP) administered by the Department of Health. In the years since it took effect, it has generated more that $70 million to support cutting-edge research at places like the University of Rochester Medical Center, the New York Neural Stem Cell Research Institute of Rensselaer, Albany Medical Center and the Burke Institute for Rehabilitative Medicine in White Plains. It has put New York on the map in terms of leadership in neurological research, attracted top-notch research talent and led to the development of valuable patents. The two initiatives I’ve described were accomplished with lightning speed. DASA, on the other hand, took eleven years. That doesn’t mean the effort was in anyway frustrating or reflected badly on the legislative process. Here is its story. In 1999, I got a call from John Meyers of Saratoga Springs. John is a gay man who had recently retired after a long career with the Department of Defense. In his retirement, John had taken up the cause of protecting the safety and dignity of gay, Lesbian, bisexual and transgendered (GLBT) youth in our schools. He created a small nonprofit called the Coalition for Safer Schools and started speaking in classrooms and attending local conferences. John wanted to do more. And so, in his researches, he learned that in 1998, the state of California had passed sweeping legislation affecting all the state’s public schools requiring the state’s Education Department to develop and promulgate rules and regulations, training requirements and a full panoply of measures designed to raise awareness of the harm that bullying and discrimination can do and encourage kids to avoid and reject these behaviors. John was quite adamant that any bill that we might propose would contain language making specific the law’s intent to protect GLBT kids. And that’s where things got interesting. In due course, I drafted the bill that John wanted and we sat down and discussed where we would go from there. I told him quite frankly that it would be easy enough to go to the chair of the Assembly Education Committee and get the bill introduced and the we could expect the Majority to pass it forthwith. Indeed, then Assemblyman Steve Sanders embraced the bill wholeheartedly. But, I explained to John, the inclusion of explicit language referencing the GLBT minority would make it highly unlikely that we could find a Republican senator to sponsor the bill. He wanted what he wanted. John Meyers is the real hero in the story of getting this legislation on the books. And so, I took him to see Senator Tom Duane, Democrat of Manhattan, New York’s first openly gay member of the state Senate, and DASA was quickly in print. And it came to pass, as it says in the Bible, that it went as I had predicted to John in 1999. The Assembly repeatedly passed the bill and the Senate would not let it out of committee. But in this instance, the years that the Legislature could not pass the bill turned into a period of extraordinary productivity. Senator Duane brought DASA to the attention of the Empire State Pride Agenda, the state’s leading advocacy organization for GLBT citizens, and that organization undertook over the next eleven years to coordinate the campaign to enact DASA. ESPA provided all administrative support including scheduling and hosting meetings, organizing rallies, keeping news of the campaign’s progress flowing. As the years went by, a growing coalition of organizations came together sharing in common concern for our children and committed to creating an educational environment in which they are safe, their dignity respected, positive values instilled and tolerance taught. Eventually, more than two hundred groups representing parents, teachers, school administrators, school boards, youth advocates and many others gathered into a powerful coalition that got to know one another and that kept the cause and purpose of DASA before the Legislature. And then, finally, came the break of opportunity when the Democrats took control of the Senate and Senator Duane was able to get his bill out of Committee, onto the Floor and passed at last. In September 2010, Governor David Paterson signed DASA into law in a very well attended ceremony at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered Community Center in Lower Manhattan. It was one of the great moments of my career to stand behind the governor with John Meyers as the governor signed the bill. Then he handed it to John who held it up in triumph.

On signing the bill, Governor Paterson said: “Every student has the right to a safe and civil educational environment, but far too often young people are ruthlessly targeted by bullies." "Bullying and harassment have disrupted the education of too many young people, and we in government have a responsibility to do our part to create learning environments that help our children prosper.” To help provide a safe and civil educational environment, the Dignity for All Students Act requires school districts to: Revise their codes of conduct and adopt policies intended to create a school environment free from harassment and discrimination; Adopt guidelines to be used in school training programs to raise awareness and sensitivity of school employees to these issues and to enable them to respond appropriately; and Designate at least one staff member in each school to be trained in non-discriminatory instructional and counseling methods and handling human relations. DASA explicitly defines "harassment" in terms of creating a hostile environment that unreasonably and substantially interferes with a student's educational performance, opportunities or benefits, or mental, emotional or physical well-being, or conduct, verbal threats, intimidation or abuse that reasonably causes or would reasonably be expected to cause a student to fear for his or her physical safety. The law also explicitly prohibits harassment and discrimination of students with respect to certain non-exclusive protected classes, including, but not limited to, the student's actual or perceived "race, color, weight, national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious practice, disability, sexual orientation, gender or sex." In the weeks immediately after DASA was signed, bullying erupted as a national issue. There has been case after case of young people bullied to death. The tragic case of Tyler Clementi, the Rutgers University student who leaped to his death from the George Washington Bridge distraught over his room mate’s Internet dispersal of a video of an intimate encounter between himself and another man shined a spotlight on a rash of suicides of gay teens. Last year out in Amherst there was the case of Jamey Rodemayer who endured two years of vicious bullying in junior high school only find it starting all over again when he started high school in September 2011. More recently, the cause was greatly advanced by the release of the award winning film “Bully.“ State, county, municipal legislatures and even the Congress have been taking up this issue across the nation. And it’s about time. Throughout the years we worked on DASA, the one thing that disappointed me was that I could never get any of my law enforcement organizations to join our coalition. From the time John first came to me with his proposal, I had seen this as a public safety issue. As a past member of the Crime Prevention Committee of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, I was keenly sensitive to the fact that discrimination in any form can lead to violence. It must be forcefully discouraged. In fact, it was while I served on that committee in 1998 that the tragic Matthew Shepard case occurred. The two young men who hung Matthew on a fence and pistol-whipped him to death apparently thought a young gay man was of no worth and no one would care if they did violence to him. That attitude needs to be sternly curbed. Over the past two years, culminating on July 1, the State Education Department convened an Statewide Task Force develop the administrative framework for the implementation of DASA. The Task Force was composed of stakeholders -- teachers, students, parents, school administrators, advocates and state and local education officials. At last, I saw my opportunity. I wrote to SED Commissioner John R. King, Jr. and urged him to invite representatives of our law enforcement agencies -- the organizations representing police chiefs, sheriffs and prosecutors -- to serve on the task force. I followed that up with a meeting with Laura Sahr, the Education Department official who was coordinating the work of the Task Force. To my satisfaction, the next time I saw a roster of the Task Force, to it had been added representatives of the Superintendent of State Police and the Division of Criminal Justice Services, the agency that is the state's liason with county and municipal police and prosecutors. Here we are today under the auspices of the New York State Bar Association bringing people together to further the efforts of the DASA Coalition to bring about the fullest possible implementation of DASA. I compliment the NYSBA for this wonderful service to the schoolchildren of the state of New York and all of you for taking the time to attend this conference and help us carry out the purpose that was first articulated when John Meyers called me with this idea in 1999.

.

|